If We Aren’t Designing for Dignity, Then What Are We Doing?

Dignity means “the state or quality of being worthy of honor or respect.”

So, when we talk about designing for dignity, shouldn’t we be talking about creating products, services, experiences, and solutions that:

spark joy and social impact across the globe?

allow all people to thrive and flourish and live their best lives?

celebrate individuality while promoting community and social connection?

support emotional, mental, and physical health?

encourage cross-pollination of ideas between industries and sectors?

promote respect and do no harm?

Well, over the course of 2 days at the 2024 Design for Dignity Conference at MassArt in Boston, MA, that’s exactly what we did.

“Dignity

/ˈdiɡnədē/

(n.) The state or quality of being worthy of honor or respect”

We designed for dignity by sparking co-creation and new ways of thinking and relating to one another.

The conference kicked off with an opening workshop, “Framework for Designing for Dignity” led by Ben Little. We split into groups and worked through a templated framework, starting with identifying a target audience we wanted to design for and identifying moments of indignity they may have experienced. As we exchanged stories of possibilities, a common theme started to emerge—our shared experiences relating to caregiving. We talked about the negative stereotype that surrounds caregiving in America, as opposed to other cultures worldwide, and the loss of identity, increased burdens, and lack of resources that caregivers often face. If caregiving for babies and children is exciting and joyous, why can’t caregiving for the elderly incite those same feelings? So, we challenged ourselves to continue to work through the framework with the following HMW statement: How might we foster a positive environment for caregivers that supports their personal needs, provides agency, maintains identity, and offers adequate resources to provide optimal care to others? By the end of the workshop, our group had bonded through storytelling and shared empathy and had started to ideate on potential solutions to our problem statement.

We designed for dignity by building empathy through storytelling.

Hosts, Chris McCarthy and Amy Heymans, shared their intentions for the conference and their vision for a future centered around designing for dignity. Attendees included physicians, service designers, policy makers, social workers, artists, musicians, educators, and more. One of the stories Amy told was about the artist, Kennedy Nganga, a member of the ArtLifting community whose artwork was featured on the branding for the conference. After suffering a spinal cord injury that left him quadriplegic, Kennedy learned to paint by wedging a paintbrush between his fingers. Highlighting Kennedy’s story is just one example of the power that prioritizing people and their lived experiences can have on inspiring others to live purposefully, passionately, and intentionally.

We designed for dignity by sharing perspectives on the intersection of design, health, and wellbeing.

During the DUO Talks portion of the conference, I presented on the topic of “Healthier Built Environments.” As a physician turned human-centered designer, I shared my perspective on the importance of creating environments that allow people to thrive and live their best lives. Because the built environment touches every aspect of our lives, it is critical that we start designing like it. That means:

understanding the influence that environments have on our hearts and minds,

acknowledging the role that poorly designed environments may be playing on the loneliness and social isolation epidemic,

co-creating with specific target populations (e.g. neurodiverse, highly sensitive, peripartum, etc.), and

incorporating evidence-based practices, like trauma-informed design and biophilic design, into our work.

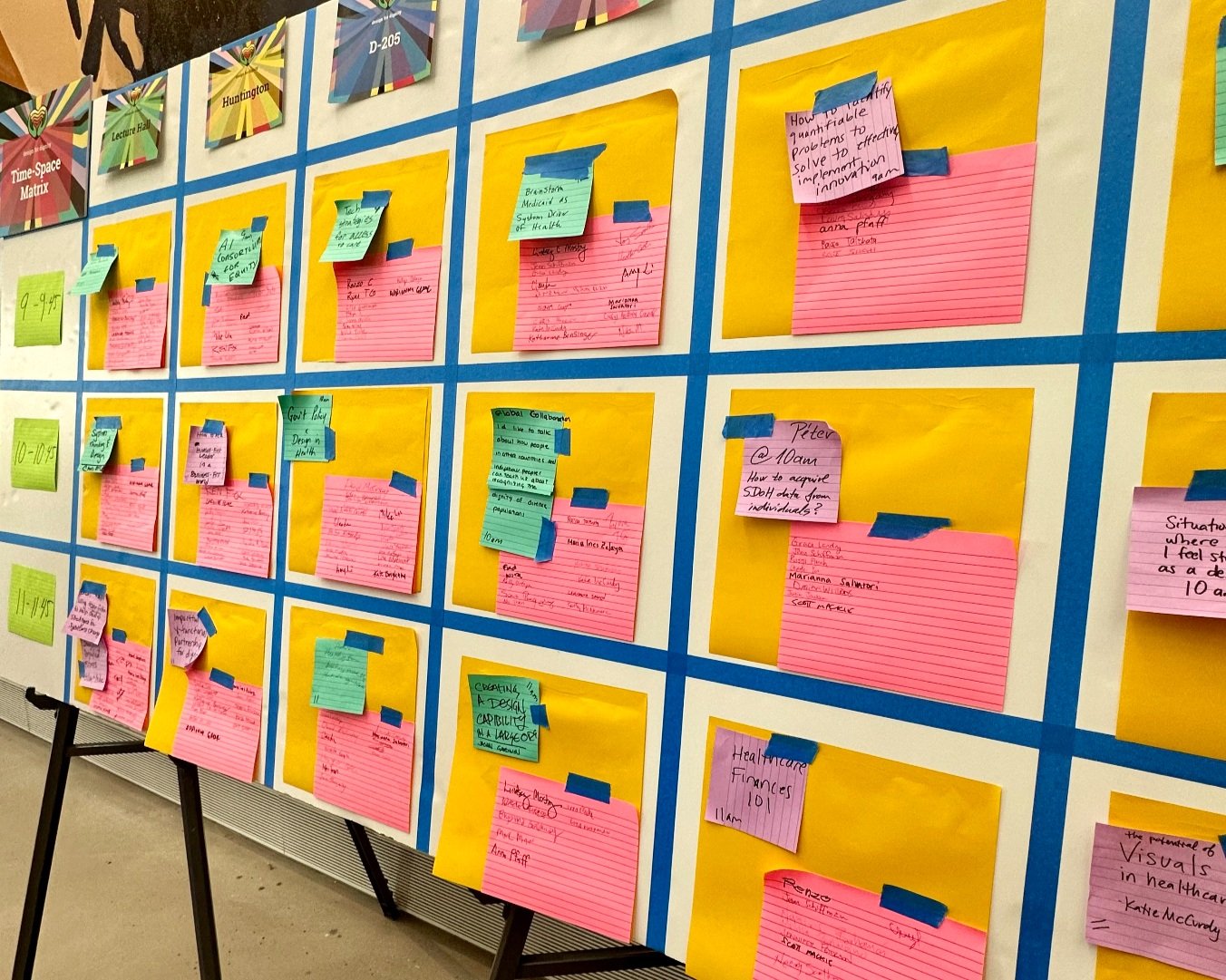

We designed for dignity by creating our own “un-conference” agenda and creating space to share individual talents and skillsets.

The first half of Day 2 was dedicated to Open Space—an un-conference agenda created by conference attendees. I was impressed by the participants’ enthusiasm for wanting to share their insights, talents, and skillsets with others. Workshop topics ranged from neuroinclusive leadership to organizational change management to healthcare finances to social determinants of health to global health and wellness. One of the most memorable workshops I attended was titled “Global Collaboration.” In a small group setting, we shared thoughts about our favorite aspects of other cultures from around the world which sparked conversations about siestas in the Mediterranean, mom hotels in Taiwan, and meriendas in Argentina. We rounded out the conversation by considering health practices that we like from other countries (e.g. universal healthcare, multigenerational living, full-paid time parental leave, user-friendly prescription packaging, etc.) and how some of those concepts could improve aspects of care here in the U.S. Overall, the conversation was enlightening, inspiring, and thought-provoking.

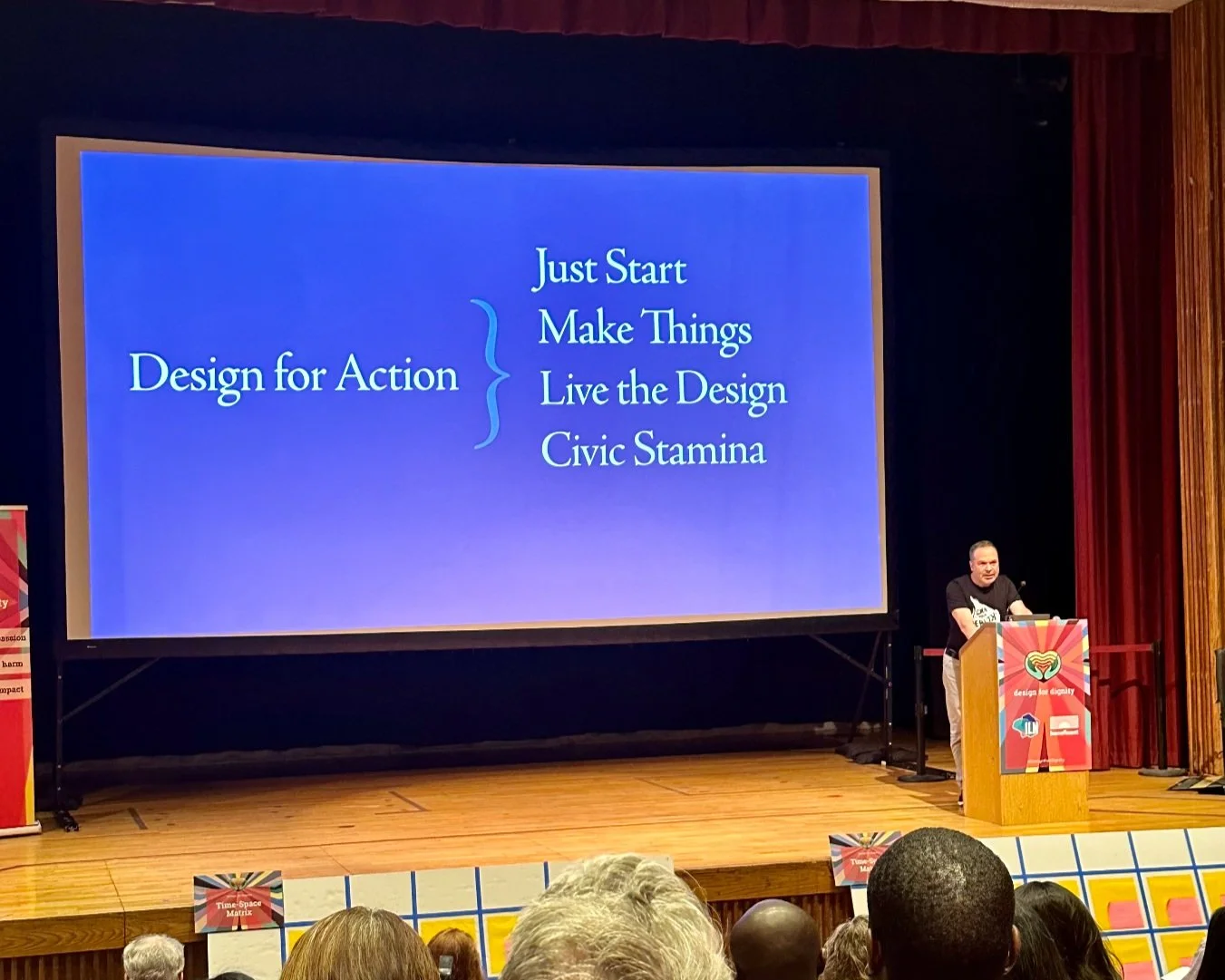

We designed for dignity by taking an oath and making personal commitments to bettering the world through design.

While the final moments of the conference were bittersweet because the agenda was coming to a close, we couldn’t have ended on a higher note. As designers, leaders, healthcare providers, policy makers, and educators, we had been tasked with making a commitment to our personal design practices and the impact we want to leave on our communities and beyond. Keynote speaker, Juhan Sonin, shared examples of his commitments to expanding access to healthcare data and designing for action.

Designing for dignity cannot happen in a vacuum, and the work cannot stop with the conference.

We must continue to conduct design research that elevates voices within communities.

We must continue to educate others about the role that design plays in shaping our environments and cultures.

We must continue to develop innovative solutions through cross-pollination.

We must continue to advocate for policy that is both ethical and equitable.

And we must continue to push boundaries and ask the hard questions….

Because if we aren’t designing for dignity, holistic health, and wellbeing, then what are we doing?